Competency F

Use the basic concepts and principles related to the selection, evaluation, organization, and preservation of physical and digital information items

While I’m sure there are certain aspects to collection management that are the same between libraries and archives; I understand selection, evaluation, organization, and preservation much stronger in an archival setting, therefore that is what I’m going to be using for this competency.

Introduction

Effective collection management in archives requires the careful selection, evaluation, organization, and preservation of both physical and digital materials. Standard archival practices and theoretical models provide the foundation for understanding these core principles. While physical and digital collections follow similar lifecycle processes, the terminology and methodologies can differ. For physical collections, this process is often referred to as the archival workflow and includes steps such as appraisal, acquisition, processing, and preservation. Digital materials, by contrast, are guided by conceptual models that outline their management and require unique considerations for long-term digital preservation.

Physical Collections

Selection & Evaluation

Archival items follow a specific process as they are brought into a collection, beginning with appraisal and accession.

Pre-appraisal is one of the first steps in an item’s journey. It helps archivists determine whether a potential donation or acquisition aligns with the institution’s mission and needs. This step can include assessing the market value of an item, which is helpful not only for purchase considerations but also for insurance purposes. Additionally, archivists assess the physical condition of the object(s); if special care or storage is needed, this information can be recorded and addressed promptly.

Accessioning goes beyond simply taking ownership of new materials. It involves evaluating the physical, legal, and intellectual conditions of the items. This includes gathering information from donors, designating storage locations, and creating initial records that capture core metadata such as provenance, condition, accession numbers, and storage locations (Davis & O’Riordan, 2021).

Organization

Once items are ready for full integration into the archive, processing takes place. According to Hackbart-Dean (2021), processing includes “accessioning, background research and [process planning], arrangement, preservation, description, publishing, and administration.” While some of these tasks may overlap with earlier stages, this highlights the iterative nature of archival work, many steps recur as materials are re-evaluated over time.

The defining aspects of processing are arrangement and description. Arrangement refers to the organization of materials within a collection in a way that reflects their significance, while description involves creating metadata that allows users to locate and understand the materials, typically through the archive’s internal retrieval system (IRS) (Stephan, 2021). These steps require the archivist to sift through content, take notes, identify themes, and decide on an appropriate organizational structure. This organization can reflect strong categories present in the materials, use the materials original order, or be chronological. Additionally, evaluation of the materials occurs during these steps as well as weeding of access or duplicate documents and closer inspection of physical conditions happen during processing. This work is highly iterative as the collection will reveal new insights as the archivist becomes more familiar with the collection.

Preservation

Preservation concerns often arise during the evaluation and selection phases but need to be fully examined and reconsidered before materials can be stored. The materials physical needs need to be taken into account and items that deteriorate faster should be kept separate from other documents, this includes newspapers, photographs, videos, and film negatives. Some of these may require cold storage or other specialized environments. An example issue that separation is trying to deter is off-gassing, where some materials emit gases that can negatively affect other materials.

Archivists must also remain vigilant for hazards such as mold or other residues, which can spread to other materials if not addressed. Even if an archive lacks access to ideal preservation conditions, implementing whatever preventative measures are available is essential for long-term stewardship.

Digital Collections

Digital materials can follow a similar process, however conceptual models have been created to better understand their unique needs such as the Digital Curation Centre (DCC) Lifecycle Model, the Data Continuum, and the Open Archival Information System (OAIS) Reference Model; such models are particularly useful as they help users understand, plan, and assess risks associated with different parts of the digital life span and related curation activities (Oliver & Harvey, 2016). The DCC Lifecycle Model in particular is useful for examining the organizational concepts as it emphasizes the continuous, iterative nature of data management throughout its lifecycle, providing guiding practices related to the curation and preservation needs of data (Higgins, 2008). One of the reasons this cyclical, iterative model represents digital materials so well is it accounts for the physical needs that are often overlooked. The problem is that technology is ever changing; so even if an item is ingested in the most current standards, within a decade or less, standards will change and technology may not be accessible due to hardware and software updates.

A Note on Collection Development Policies

Policy development is essential to ensure the long-term management of collections. Archival teams should create comprehensive policies that address collection development, acquisition, metadata standards, emergency preparedness, and preservation practices. These policies provide structure for day-to-day operations and can support institutional future planning.

Evidence

UNO Internship: Collection Processing – NAS Finding Aid Documentation

As mentioned previously, during the summer of 2024 I completed a 100-hour internship at the University of Nebraska at Omaha Archives and Special Collections. The internship included working with processing, outreach and digital archivist and three informational interviews. For this piece of evidence I will be summarizing the work I did in processing.

Under the supervision of the processing archivist I inventoried, arranged, and described the UNO Native American Studies (NAS) Program Records and created metadata for their website through ArchiveSpace. This task gave me first hand experience with all of the main steps in processing a small collection by sorting the material by types and subject matter, selecting items that should remain in the collection or should be re-homed elsewhere, evaluating items quality in case items require extra attention to ensure proper preservation, preparing the items for long term storage in appropriate archival folders and boxes, and describing the collection in detail on ArchiveSpace (including collection, folder, and item level descriptions).

I’ve included links to a presentation I gave to the UNO Archives and Collection staff on my last day at the archives as well as a link to the finding aid for the NAS Records. Under the Finding Aid & Administrative Information you’ll find my name under author.

This work demonstrates my knowledge of this competency on all fronts as I worked with the materials through the full cycle of processing minus acquisition. Relevant discussion of the processing includes 1:19-6:00 in the presentation.

Lace Museum Internship – Archive Creation

Starting in March 2024, three SJSU students and myself where selected to help build an archive for a small museum in Fremont, California. This monumental endeavor is still underway, currently I’m at just over 500 hours of work on this project. I’m submitting a poster proposal for the SAA 2025 annual meeting that covers this project, screen shots from an item I arranged and described and various process photos (compF_letter.pdf & compF_proposalAbstract.pdf).

This project has helped me grow as an LIS professional in unique ways. We started with a room of unmarked boxes, filled with an assortment of items such as patterns, samples, lectures, photos, pamphlet, catalogs, advertisements, correspondence, newsletters, and notes. Our first task was to do a gross sort making piles of related items while taking note of categories that stood out to us, and trying to keep things together if they looked like they had an intentional collection or series relation. After careful consideration we settled on more definite categories that became our different collections including: newsletters, museum history, lace history, people, photos, videos, lectures, newspapers and patterns. Some of these are separated as the item material has different variables that should be taken into consideration for proper storage like the newspapers, photos, and video, while other collections have to have mixed materials as the connection between the items are the most important aspect for the collections series. This is the case for the people files which tell the individual stories of important lace makers and contributors. This collection houses a majority of our lace samples and thus is where the lace preservation system comes into play and will be talked about more in the next section.

After this second gross sort, we split into two teams to tackle the first sections; I worked with a partner to get through the newsletter section. This process mimics the work I did at UNO processing the NAS department records, except that these materials were much more uniform as almost everything in this section was a newsletter created by the lace museum and it’s predecessor….. Additionally, as the museum is quite a bit smaller with a niche subject matter, the individual item records are a bit more detailed in there description. So essentially, this is the work we’re still doing now. As a group we’ve completed processing the newsletters and museum history collections, and have moved on to photos and people.

This project is once again, a bit difficult to separate out who did what as many of the sections where done in pairs or as a whole group to make use of our collective knowledge, though the item I’m showing is an example of a piece I did myself. This project, like the UNO processing project, covers most of the processing process plus allowed us to build the system from the ground up which was informative, if a bit challenging.

Lace Museum Internship – Lace Preservation

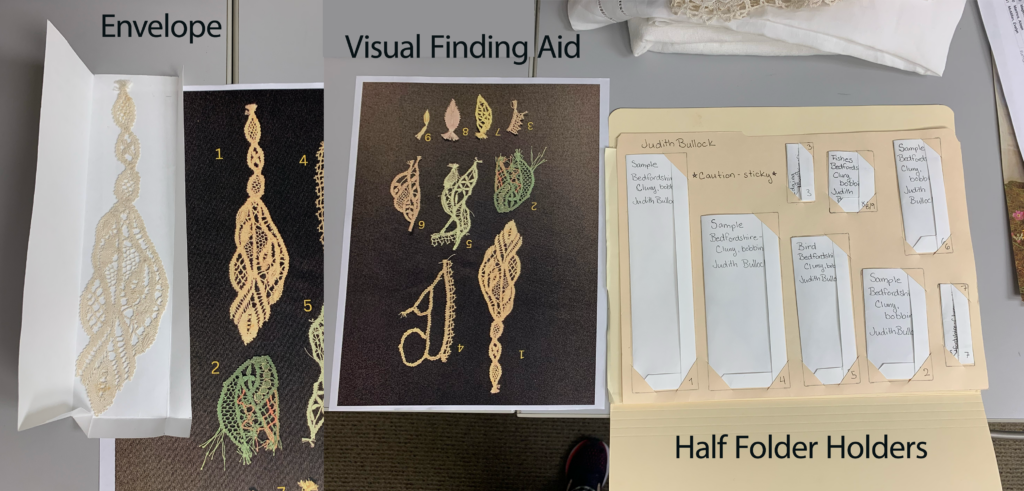

This next piece of evidence might be seen an extension of the last piece of evidence as it is the housing fix I came up with to safely organize the mixed material items of lace samples that showed up primarily in the “people” collection of the archive. Included is a video showing how the lace preservation system works and a few associated photos.

These are deceptively simple, DIY looking pockets and holders for the pieces of lace that aren’t large enough to be put into the collection, but can still be useful to understand a part of a persons lace journey. I started by brainstorming with the other students and the museum director about the requirements for this system. They needed to be:

- supportive and hold the lace in a flat state;

- breathable, as textiles need sufficient air flow to ensure long term preservation;

- relatively inexpensive;

- easy to open and handle by older lace enthusiasts and researchers;

- non-adhesive based;

- able to fit into the file folders

I looked for preexisting options, such as envelopes and photo protectors, but these all had some sort of adhesive siding or weren’t made of breathable material. There were a couple more pre-built options but none of them were exactly right. Eventually, I started looking into individually made origami envelopes, but these use a significant amount of paper, and as the paper needed to be specific archival safe buffered paper that would be a significant cost and quite bulky. Next up I looked at paper techniques that used cutting, but these were quite intricate. Finally I just started fiddling around with the techniques I had already learned from the previous paper folding tutorials and came up with the current system.

This project took several days to figure out and pushed me to deep dive into the unique preservation needs of textiles.

INFO 284: Digitization – Collection of Northern California Menus Paper & Presentation

This last piece of evidence to shows my understanding of competency F focuses on the selection, evaluation, and preservation of menus via a project created for INFO 284 and includes a paper write up for the project, our slide deck from the group presentation and a tour of our website collection (compF_menuDigitizationPaper.pdf, compF_menuDigitization & NCCollectionTour.mp4).

This project occurred piece by piece over a semester. Our group started out as four but we had one member drop mid semester which was a new experience for me. We needed to readjust our roles and our professor helped us scale down the project accordingly. We ended up with 30 fully scanned menus with associated Dublin Core metadata including OCR transcription via Adobe Acrobat. Our collection was uploaded in a temporary website through ContentDM.

There are a few things that make this project different from the others I’ve already talked about. First, the material for our collection was our choice but we needed to consider legal use and possible copyright issues. Second, this is a physical collection that was digitized. While we were allowed to have just one individual do the digitizing which could allow for a more uniform collection, our group wanted everyone to have the full experience of scanning items and figuring out scanning criteria. This meant our selection criteria had to accommodate items that could be scanned via a standard office or home scanner, and that the collection had to be local for each of us. This is how we landed on takeout menus from Northern California restaurants as all members are in the area, but not all within the Bay Area. Additionally, we chose to use mom and pop restaurants verse chains as this is more indicative of local food culture and is less likely to have any copyright issues arise. However, once we started collecting menus it became clear that many local places aren’t making or using takeout menus anymore. This caused us to widen our selection criteria to include local chains.

Once again, this was a group project where many of the decisions were made through conversation after individual research. Within the collection we each gathered ten menus, digitized them, uploaded them to ContentDM, and created the metadata for our own menus. To ensure constancy we had guidelines, but then also assigned one person to each metadata type to double check that they all followed the guidelines. Each of the sections in our paper had associated modules of our class, after those lectures and readings we’d meet and discuss the important factors that we all felt impacted our collection and took notes in a group document. Once we finalized our collection online, we split the writing of the paper and slide deck into three sections. I was the primary writer for the Metadata and the Challenges and Successes Sections (pp. 9-14) For the Slides, the information I presented on and wrote about start on slide 11. I also filmed and created a small script for the collection tour. Additionally, the metadata I created for the menus I selected and added to our collection can be found in this spreadsheet.

Conclusion

The foundation for many libraries and archives boils is their collection of materials. When building these collections it’s imperative to consider the nature of the materials and the user at all stages of selection, evaluation, organization and preservation.

Going forward when I want or need to learn more about collection management there are so many different options and really depends on the collection type; for example I can check out the SAAs quarterly magazine Archival Outlook to read about different collections, connect to other members through the portal to ask specific questions, or read journal articles that cover new techniques within these areas.

References

Davis, R. K. J. & O’Riordan, M. (2021). Accessioning. In P. C. Franks (Ed.), The handbook of archival practice (pp. 86-90). Rowman & Littlefield.

Hackbart-Dean, P. (2021). Processing. In P. C. Franks (Ed.), The handbook of archival practice (pp. 174-177). Rowman & Littlefield.

Higgins, S. (2008). The DCC curation lifecycle model. The International Journal of Digital Curation, 3(1): 134-140. https://doi.org/10.2218/ijdc.v3i1.48

Oliver, G. & Harvey, R. (2016). Digital curation. (2nd ed.). ALA Neal-Schuman.

Stephan, W. A. (2021). Arrangement and description. In P. C. Franks (Ed.), The handbook of archival practice (pp. 142-145). Rowman & Littlefield.