Competency L

Demonstrate understanding of quantitative and qualitative research methods, the ability to design a research project, and the ability to evaluate and synthesize research literature

Introduction

Research is an integral part of libraries and archives. LIS institutions are often among the first locations visited to start research, and ultimately where much research may reside once completed. This is just one reason why it is important for information professionals to understand the various types of research and how they are conducted.

Methodology: Qualitative & Quantitative Research

Understanding research methodologies as a LIS professional is essential. Whether you’re conducting research or simply keeping up to date with best practices, understanding the differences between methodology types is central to grasping how the research is constructed. It helps one understand the kinds of practices that were used, the types of data collected, and may even provide insight into the epistemological underpinnings of the research.

Methodology has been referred to as the pathway to knowledge by Onwuegbuzie & Frels (2016). It’s not just about how the research is done, but also the assumptions attached to how it is done. Generally speaking, there are three main types of research methodologies: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. These are distinguished by a few key differences, include the type of data collected, how it is gathered, and subsequently how it is analyzed. Additionally, methodological choice influences the kinds of questions being asked and ultimately shapes how research can be conducted.

Quantitative research involves data in the form of numbers and measurements (Punch, 2009). These studies are often used to explore and explain situations, typically through the direct collection of data to test a researcher’s hypothesis or theories (Onwuegbuzie & Frels, 2016). Qualitative research, on the other hand, generally includes non-numerical data. According to Punch (2009), this usually means words, although Onwuegbuzie & Frels (2016) note that it can also include observations, documents, photos, or even drawings. This type of research is often more directly influenced by the researcher’s worldview, as it relies on interpretation of situations or interviews. These two types can and should be combined when appropriate; this is known as Mixed Methods (Punch, 2009).

Research Process

Choosing a research methodology is only one step in designing a research project. When considering research design, there are many models researchers can choose to follow.

Radsliff (2023) explores the process in a natural, cyclical model, suggesting four main stages: exploration, strategizing, action, and analysis and revision. This structure allows researchers the flexibility to pivot between activities, without feeling bogged down by a rigid linear approach. The process as a whole can be seen as iterative; researchers should feel free to move between steps as needed rather than according to a prescribed sequence.

An example of a more linear research approach is Onwuegbuzie & Frels’ 7-step model for literature reviews, which includes: “exploring beliefs and topics; searching, storing and organizing information; selecting & deselecting information; expanding the search; analyzing and synthesis; and presenting.” (p. 54, 2016) Having concrete, linear steps provides researchers with a direct path that may be easier to follow.

While these models look at the researcher’s direct actions, considering the entirety of the Research Lifecycle can support LIS professionals that provide research support services. A clear, easy to understand interpretation can be seen in the APH Quality Handbook (Ghouch et al, 2003). In the handbook there are three main phases that are articulated: Design, Plan & Propose; Set-up & Conduct; and Reporting, Review & Knowledge Utilization. While the Set-up & Conduct stage is what most people think of as “research,” the other two stages articulate the more nebulous stages that occur while researchers are preparing for research and then what is happening with their products after research is complete. Additionally, a layer encompassing these stages: Compliance, Training & Supervision takes into account how these support structures need to be ever present throughout the research process. This more complete view allows institutions to facilitate things like researchers motivation; preservation of manuscripts and data; access and promotion of research materials; and more.

Evaluation & Synthesis

No matter the model chosen, evaluation and synthesis of data will be involved in any research project. Most published works include a literature review to ground the work within the context of its field. Understanding evaluation and synthesis is especially relevant in this stage of the process (UNC, 2023). A comprehensive search is conducted during the literature review to define key concepts, gain insight into recent developments in the field, and identify gaps in the existing literature. This search is often iterative; researchers review results from multiple searches to determine whether they satisfy the project’s needs; this can involve quick evaluation of the title, abstract, or skimming the text (Meredith, 2015). The process should continue throughout the in-depth analysis of material.

Once the material has been deemed relevant and reliable, its content must be understood. Through synthesis researchers aren’t simply summarizing information, but transforming it into a new idea (Purdue Writing Lab, 2018; Meredith, 2015). This can be achieved by applying it to their own understanding and experiences, or by putting one source in conversation with another through juxtaposition of their ideas.

Use for LIS Professionals

Competency L asks future professionals to understand how research is conducted. While academic librarians, special collections librarians, and archivists may be the most overtly affected by this competency, all information professionals are bound to eventually deal directly or indirectly with research, whether it is their own or someone else’s. By understanding methodology, design, evaluation and synthesis, information professionals can more effectively teach or support others in their research endeavors or conduct their own projects as needed.

Facilitating traditional research is important, but it’s not the only context in which these skills are relevant. User-centered initiatives may require gathering information about one’s user base; this is a form of applied research. Similarly, staying current with trends in the field requires the information professional to stay engaged with the literature as it evolves. Practicing research ultimately hones skills to critically engage with and contribute to the literature.

Evidence

Info 200: Information Communities – Literature Review Matrix

The first piece of evidence to showcase my understanding of competency L is the Literature Review Matrix created to organize and understand the research materials used in my literature review of the video game preservation community for INFO 200 (compL_LitReviewMatrix.pdf). In order to create the matrix I compiled a list of all of the relevant research articles via their citations. Then filled in the corresponding boxes of the “They said” section of the matrix that helped me evaluate each article before moving on to the “I say” section where I started to analyze each source’s information. Ultimately this exercise helped me evaluate my resources and laid the foundation for successful synthesis within the final literature review. Additionally it was great practice in preparation for my research manuscript in INFO 285.

Info 285: Applied Research Methods: Literature Review – Research Manuscript

This research manuscript was the culmination of two years of work starting in INFO 285 and then revised multiple times while going through the publication process. The manuscript epitomizes my engagement with research design and mastery of evaluation and synthesis of literature (compL&O_researchManuscript.pdf). In this class I paired up with another MLIS student for the semester; we discussed research methods and went through the process to complete a Comprehensive Literature Review (CLR) on international perspectives of research data management services (RDMS). We followed the 7 steps outlined by Onwuegbuzie & Frels as outlined in the section “Research Process.”

By working through these steps we came to understand not only our topic but where our biases and past experiences situates us within the conversation. This project is an example of qualitative research that exemplifies my evaluation, analytical and synthesis skills.

Our search included thorough exploration of five databases, multiple related websites, and snowball searching. Collected materials were subject to title and abstract evaluation where non relevant sources were subsequently weeded (more about this process can be found in the Research Strategy section of the paper). Sources were analyzed and sorted into categories and subcategories that we felt encompassed the main areas that libraries and research institutions need to cover for proper RDMS implantation, see Figure 2: RDMS Area Categories and Table 1 & RDMS Challenges Breakdown (pp. 6-7).

While the final manuscript has multiple revisions by both parties to insure cohesion of analysis and a unified voice, making it difficult to see our distinct contributions. For my part, during the initial search I worked on completing searching in Academic Search Complete, Gale OneFile Information Science, and Science Direct. Once we found our 30 sources we both read all 30 to come up with our codification system. We then split the list into two so that each of us had 15 articles to analyze, then switched to check that we agreed with each other’s categorizations. The initial sections for writing were split as well; I wrote the first draft for the sections: Introduction, Research Strategy, Human Interaction (and its subcategories), Technology (and its subcategories), and Conclusion.

This manuscript embodies my ability to evaluate and synthesize LIS literature, proficiency with qualitative methods, and an example of designing then completing a research project.

Info 246: Tech Tools: Information Visualization – Story Telling with Information Visualization

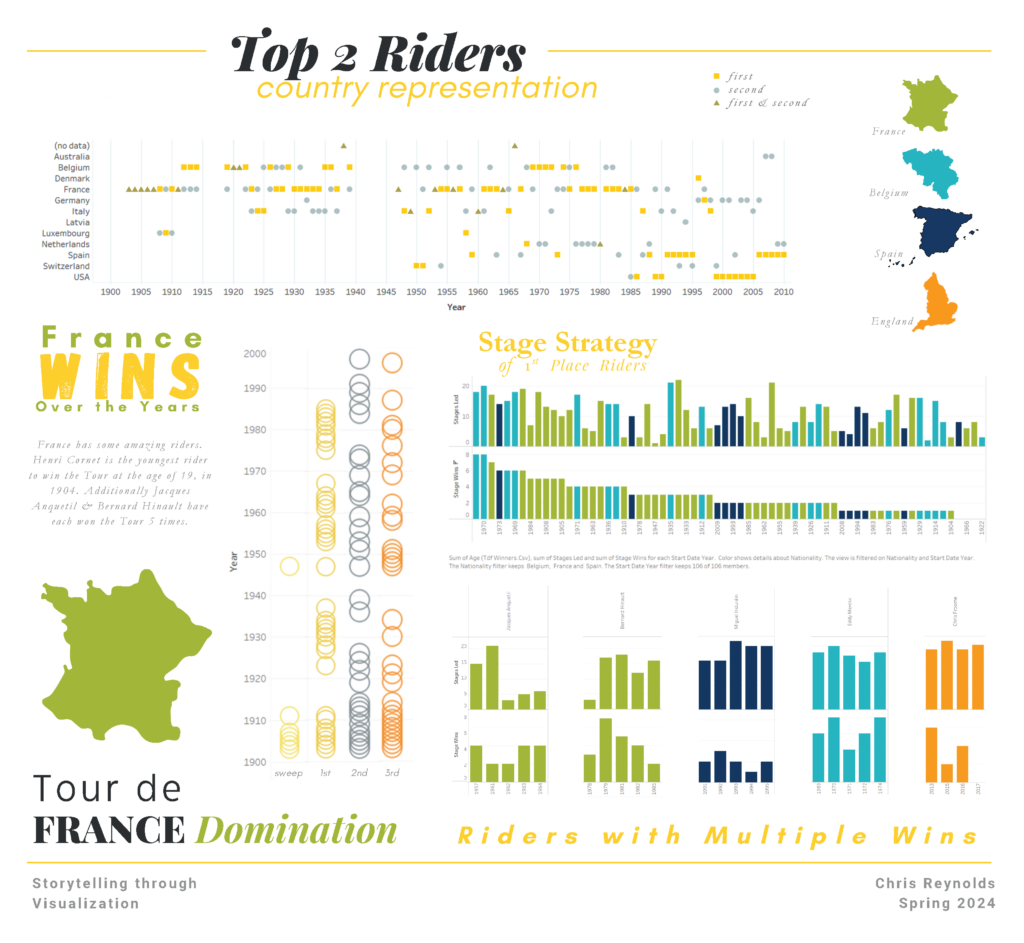

The last piece of evidence to showcase my understanding of competency L is a two-part solo assignment analyzing and visualizing Tour de France data (compL_TdFranceSlides.pdf, compL_TdFrancePoster.png, & compL_TdFrancePosterReflection.pdf). These pieces are examples of work with quantitative data that illustrates a different aspect of data synthesis. Analysis done in the initial steps of this project include basic calculations, manipulation of excel files, and basic use of Tableau. By working towards visualizations instead of a paper, it was critical to understand the intended audience, information organization, and narrative structure.

While this assignment doesn’t directly deal with LIS data, similar techniques could be used to present data such as usage of library services and materials; event turnout and outcomes; or patron needs based on census data or surveys. This evidence demonstrates my ability to analyze and employ quantitative data.

Conclusion

Knowing how research is conducted is important for all LIS professionals, but for me specifically it’s essential as I’m hoping to potentially work in an academic library or an archive. This means I will be working with individuals conducting research on a regular basis. My understanding of the research lifecycle will allow me to provide support to patrons engaging in their own research journey. Additionally I may also need to engage in my own research.

Going forward it’s important for me to keep up with the current literature on various research processes and potential services I can provide to help patrons. This will include reading the literature, taking courses when needed and going to conferences to keep up to date with current issues and trends in this area. Connecting with other professionals in the LIS space through membership of ACRL, ASIS&T, or SAA (depending on where I am employed) will connect me to those resources and conversations.

References

Ghouch, Y., Riet, S., Takkenberg, G.M., Laan, D., Boer, E., & Jahfari, S. [Eds.] (2003). Amsterdam Public Health Institute Quality Handbook. University of Amsterdam. https://aph-qualityhandbook.org

Meredith, C. (Ed.). (2015). Choosing & using sources: a guide to academic research. The Ohio State University. https://ohiostate.pressbooks.pub/choosingsources/

Onwuegbuzie, A., & Frels, R. (2016). Seven steps to a comprehensive literature review: A multimodal and cultural approach. SAGE.

Punch, K. F., & Oancea, A. (2014). Introduction to research methods in education.

Radsliff, K. (2023). Navigating the CLR Research Manuscript [Infographic]. Prezi. https://prezi.com/i/view/ODTA4XOievc0DTfZmKmv

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (2023). Literature reviews. Unc.edu. https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/literature-reviews/