Competency N

Evaluate programs and services using measurable criteria

Introduction

The importance of evaluation cannot be overstated. Evaluation, assessment, and related concepts have been previously discussed in competencies D and L. LIS institutions use evaluations to better understand their users’ needs, how often their programs and materials are being used, and, ultimately, to reinforce organizational goals. Feedback is foundational to improving programs and services. Even if a librarian has worked with a specific demographic for a long time, that doesn’t mean they automatically understand them. In UX circles, the phrase “you are not your user” is often used to emphasize this point. Effective evaluation in LIS settings relies on clear, measurable criteria that reflect both user needs and institutional missions.

Evaluation

Matthews (2018) defines evaluation as “the process of determining the results, costs, outcomes, impacts, successes and other factors related to a library’s collections, programs, services, or resource use” (p. 255). With this direct knowledge, organizations are able to make data-driven decisions. This means that when asked to defend their programs and services, they can point to a paper trail and supporting data.

In addition, assessments track library activity over time. They show what programs and resources are being used, provide ways to compare different offerings, consider where the organization should focus its efforts, and create metrics that demonstrate impact; all of these can be useful for advocacy. They also encourage ongoing reflection for future planning efforts (Matthews, 2018). As Bakkalbasi (2017) notes, the scope of these activities can vary widely; for instance, instruction librarians may assess student learning outcomes, while website administrators might track site visits or digital tool usage.

Collecting Measurable Criteria

Choosing what to evaluate is critical. While organizational research can help libraries improve, measuring the wrong thing wastes both time and money. Evaluation takes planning, and the quality of the data collected depends on the questions being asked. If the wrong questions are asked, the resulting data may not be as relevant.

To determine what to measure, librarians should consider:

- What problem is being addressed?

- What is the objective of the study?

- How will the study be conducted?

- What methods should be used to interpret the data?

Tools

A variety of tools are available to support evaluation in LIS settings, helping professionals provide consistency and credibility in their assessments. Bakkalbasi (2017) covers a number of these tools including the ANSC data dictionary which offers standardized terminology around metrics; ISO Library Performance Indicators, which provide widely used methodologies for measuring performance of library services, offering structured approaches to identifying strengths and areas for improvement; and LibQUAL+, a survey-based bench-marking tool designed to measure users’ perceptions of service quality. These tools support evidence-based decisions by helping libraries understand gaps between user expectations and their actual experiences (Bakkalbasi, 2017).

In addition to these larger digital tools, librarians can use homegrown techniques such as local questionnaires, feedback boxes, think-aloud protocol sessions, or ethnographic observation. These methods allow for a more nuanced understanding of local user experience, capturing insights that might otherwise be missed. Libraries can pick and chose which tools fit there evaluation questions to develop a more holistic view of how their services are functioning and where they can improve.

A Note on Data

When collecting data through assessments and evaluations, LIS professionals must carefully consider privacy and ethical concerns. For example, surveys involving human subjects require an understanding of the ethical implications involved. Programs like the CITI Human Subject Research course can help ensure proper training.

Furthermore, it’s critical to consider how questions are phrased. Researchers may unintentionally frame questions in ways that reflect personal bias or steer respondents toward certain answers. Similarly, with quantitative data, there’s a risk of over-analyzing or manipulating data to suggest relationships that don’t truly exist, whether done intentionally or not. Awareness and reflection are essential to prevent these issues.

Evidence

INFO 210: Reference and Information Services – Reference Services Evaluations

My first item to show mastery of competency N is a series of discussion posts from INFO 210, Reference and Information Services, where I observed and evaluated different library’s reference services via various interfaces (compN_ReferenceServicesEval.doc).

By using the Guidelines for Behavioral Performance put out by the Reference and User Services Association (RUSA), I was able to evaluate a range of reference experiences including a past in person session, a phone interview, and an email reference interview based on current professional standards. These discussions involved me taking on the role of a library user, gathering information via my interactions, then reflecting on my experience with the guidelines in mind. During each evaluation I considered the individual interactions in terms of RUSAs five areas: visibility and approachability, interest, listening and inquiring, searching, and follow-up (RUSA, 2008).

For the first assessment I examined a memory of a liaison librarian experience at De Anza Community College, I step through the interactions and make note of when part of the interaction lines up with one of RUSAs core areas. In the second assessment I called the San Jose Public Library via their synchronous phone reference service, I start by recounting the experience asking for help finding resources to bolster graduate level note taking then moving through RUSAs areas more methodically I evaluate the interaction on each level. The last assessment I contacted San Jose State’s Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Library through the E-mail Us hub on their website and did a combo of the two previous methods where I talked through the interaction and pointed to the different areas by its associated number.

This item shows my knowledge and understanding of evaluating a library service using assessment criteria and tools, specifically the RUSA guidelines. It also reinforces to me the idea that the more you work within a system of evaluation the easier it’ll become and the assessments may become more detailed and specific.

INFO 220: Visual Resources Curation & Arts Librarianship: Digital Image Collection Evaluation

The next piece of evidence that illustrates my proficiency in evaluating programs is an evaluation of an online collections user experience written for INFO 220,Visual Resources Curation and Arts Librarianship, reviewing the collection of Japanese Animated Film Classics from the National Film Center (NFC) in Tokyo, Japan (compN&O_digiEval.pdf). This assignment asked students to evaluate and reflect on an online image collection and the UI used to explore the collection by using guidelines created by Chang, Bliss, & Altemu.

This evaluation included an in-depth user experience audit including the categories such as how can the collection be sorted and searched; what metadata elements were included, what type of navigation system is available, what type of visual structure was used and in what ways the items could be downloaded (Chang et al, 2019). While not all of the categories were relevant to the collection I chose, in inspecting and reflecting on this collection’s presentation I was able to understand why these elements are useful to consider when creating a digital collection. It’s really not enough to provide the items without considering your audience’s needs and expectations. Additionally by providing multiple ways of searching and interaction points, people viewing the collection can craft an experience that is useful for themselves.

All in all, this project allowed me to look at digital collections, UI, UX, collection and searchability. Furthermore, I was able to look at these elements as created by an institution outside of the U.S., which was useful to broaden my understanding of how these concepts may or may not apply to non-English collections.

UNO Internship: Digitization – Time Trials Write Up

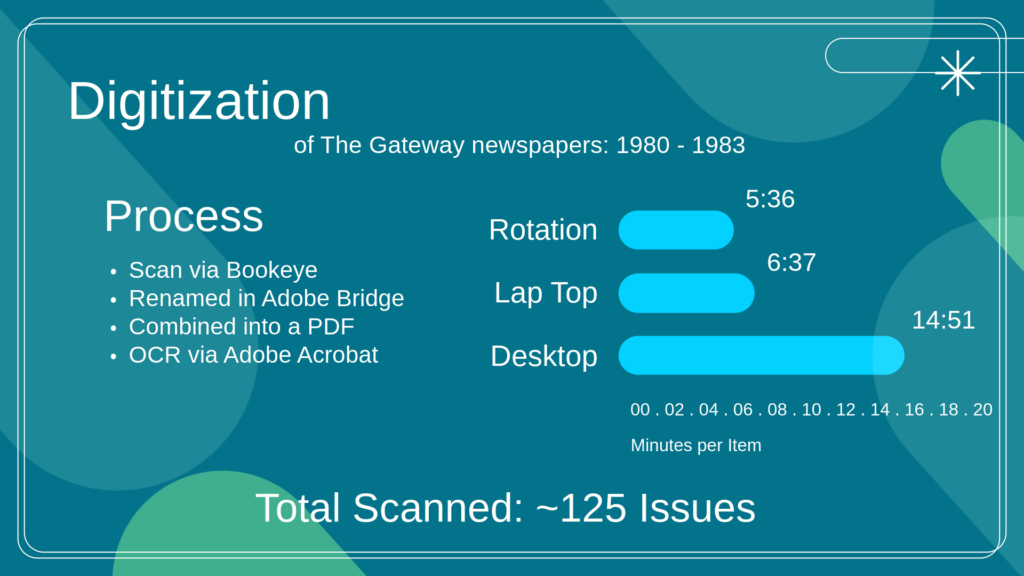

The next piece of evidence in support of understanding the importance of using measurable criteria to evaluate programs and services is a short report written for the University of Nebraska at Omaha (UNO) Archives and Special Collections regarding an assessment of the archives computer capacity (compN_TimeTrailWriteUp.doc & compN_TimeTrailSlide.png).

During my summer internship at UNO one of my projects was to help re-digitize some of the schools historical newspaper collection. This processes included a number of steps including:

- Scanning the pages via a Bookeye (an over head scanner)

- Renaming and making sure the files where in the correct order in Adobe Bridge

- Fixing any extreme visual issues in Adobe Photoshop

- Combining the files into a single PDF per newspaper issue

- Creating Optical Character Recognition (OCR) text in Adobe Acrobat

- Organizing the files into the correct folders within UNOs database

As I became acquainted with the process, I noticed it took a significant amount of time for the UNO computers to complete the tasks. While the files were quite large, which can slow down processing times, it seemed to me that this was significantly longer than any computer I’d used in the past decade. So I asked if I could use my personal laptop to perform the file renaming and adjustments. Once granted I noticed significant difference in my working speed and decided to create time trials as a way to measure the differences between working with the two machines; by working on a newer machine I was able to half the amount of working time per issue. In creating standardized time trials and documenting my processes I was able to create items of evidence that the UNO Archives and Special Collections could bring to their management and advocate for a newer machine.

This assessment highlights the importance of having tangible assessment data in cases where a department is advocating for new equipment or funding. Furthermore, evaluations don’t have to be expensive or time consuming; in this case I was able to set up the time trials with equipment I already had access to and during a time where I was already performing tasks for the collection. Additionally, while the slow computer was evaluated with the archivists time in mind, it’s also the computer that’s used by students and researchers when they come into the archive; there for it being slow negatively impacts multiple areas for the department: taking time away from the archivist in charge of processing, availability of resources through the digital collection, and user experience at the archive.

Conclusion

As I move into professional work in libraries and archives, evaluating the programs and services that I provide will help me reflect on my work and understand how to improve going forward. While assessment can take time, there are ways of integrating this practice into my work.

Going forward I know that I will need to keep current with industry practices in this area. In order to do that I can attend conferences or webinars and receive new updates from organizations like the ALA, ACRL, and ARL.

References

American Library Association. (2008). RUSA guidelines for behavioral performance of reference and information service providers. ALA. http://www.ala.org/rusa/resources/guidelines/guidelinesbehavioral

Bakkalbasi, N. (2017). Assessment and evaluation, promotion, and marketing of academic library services. In T. Gilman (Ed.), Academic librarianship today (pp. 211-220). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Chang, R., Bliss, D.F., & Altemus, A.R. (2019). Usability guidelines for an online image database. Journal of Biocommunication, 41(1), 14-23. https://doi.org/10.5210/jbc.v43i1.7874

Matthews, J. R. (2018). Evaluation: An introduction to a crucial skill. In K. Haycock & M.-J. Romaniuk (Eds.), The Portable MLIS: Insights from the Experts (2nd ed., pp 255-264). Libraries Unlimited.